Against the baseball fanboys

It’s October 29, 2022, and I’m weary of reading comments from fans that the Phillies don’t belong in the World Series (or perhaps even the postseason) because they won “only” 87 games to Houston’s 106. I’m getting numb to one sportswriter after another say “it isn’t about the best team, it’s about the team that gets hot.” And I could be channeling a bit of guilt because I’ve been on the other end of those comments. I’ve gnashed my teeth when a team with a record that’s barely above “losing” was in the postseason. I’ve hurled insults at the teams which in essence bought their way into the Series and the Championship (looking at you, Wayne Huizenga). But I think there’s a difference this year, and I think I’ve come to understand the game more.

Ironically in 1997 this same Houston team got into the postseason with a record (84-78) that was only four decisions away from being a losing season and worse than this year’s Phillies! Houston managed to win its division that year, the National League Central. Based on season records, the second-best team in the NL, the Florida Marlins, got in only because of that relatively new concept, the Wild Card, because the Braves placed first in the NL East. Houston lost in its very first round. Even though the Atlanta Braves won nine more games during the season, the Marlins beat them in the NL Championship Series and then beat the Cleveland Indians in the World Series. The Indians (now Guardians) finished the regular season 86-75, only two wins (but three losses) better than the Astros…and the Indians were in the World Series. Wait, what? We’ve got people complaining about the Phillies’ record of 87-75? Where were they in 1997? Maybe they weren’t born yet?

I would like to let these baseball fans off the hook–after all, it takes a bit of time to look up records from 25 years ago, and it takes age to remember them, and I have both. However, you’re just being lazy when you ignore what happened in this season! Consider:

- With hindsight, no intelligent baseball fan can dispute the Phillies were finding their way as a team in the first 8 weeks of the season. Their two biggest offseason acquisitions, Kyle Schwarber and Nick Castellanos, signed on March 20th and March 22nd, respectively. Games began to count less than three weeks later on April 8th. Did other teams sign marquee players that late? I don’t know without looking it up, and I don’t care. If there were others, those players and those teams also started with a handicap. The Phillies’ signings were BIG. Every fan should be aware of them.

- In addition to starting with a bit of a handicap to integrate the star players, when manager Joe Girardi received his walking papers before the June 3 game, nearly every major baseball writer made it clear he lacked patience with younger players. The Phillies had a number of experienced veterans–Bryce Harper, Castellanos, Schwarber, Rhys Hoskins, J.T. Realmuto, Zach Wheeler, Aaron Nola, Jean Segura, Didi Gregorius–but it takes eight to play the positions and Alec Bohm, Bryson Stott, Matt Vierling, Mickey Moniak all needed more than Girardi gave them. (Ironically, Girardi lobbied for some of those guys to be on the roster!)

- Since the beginning of June, less than eight weeks into the season, the Phillies posted a 66-46 record, a winning percentage of .589, while the teams they faced in the postseason did this: Cardinals 65-48 (.575), Braves 75-34 (.688), and Padres 59-54 (.541). Obviously, only Braves fans should feel shocked by watching the Phillies dispatch their team…if we’re really saying that a few wins one way or the other makes a big difference in the postseason. And those same Braves fans might want to recall their reigning World Champions went four months last year without a winning record! Somehow they got to the postseason with an 88-73 record that was (wait while the author does some heavy math) only one win more than the Phillies this season? Seriously? Where were the whiners last year? Oh, I see–because the Braves won the division with that record it’s all okay?

- More importantly the head-to-head records show something interesting. Of the NL teams in the postseason, the Phillies bested the Cardinals 4 games to 3 and beat the Padres 4-3. Only the Braves have a right to complain a bit since they beat the Phillies 11 out of 19 meetings. Some games against the Braves were lopsided, some were close, i.e., a typical series. What if the Phillies had played the two teams they didn’t meet in the postseason? Well, they beat the Dodgers 4-3 (including a sweep in Los Angeles). The Mets? Funny thing: some crazy scheduling decisions were made by a back-office dweeb when assembling the schedule this year (and maybe that explains many a team’s record). The Phillies encountered the Mets 12 times during those first eight weeks when things were just coming together, April 8-May 31. And Philadelphia got thumped, winning only three of those games. And you know what? When they met the Mets in August for seven more games? They got thumped some more! I don’t think I was only Phillies Phan hoping the team would not encounter the Mets in the postseason. My point? If you consider the seven-game series against non-divisional opponents (Cards, Dodgers, Padres) as if they were postseason contests, the Phillies were victorious in all of them. The Phillies played the Braves tight in quite a few games, so their fans shouldn’t be super-surprised the Phillies managed to beat them this fall. And thank the good lord we didn’t play the Mets. (Now, the Mets fans have a good complaint against the Padres, but that’s for their fanbase, not this one.)

The only thing left is to comment on the first game of the World Series where the Phillies shocked the Astros fanbase by somehow winning the first game. One should note that in the very first meeting of these two teams, the Phillies backed Aaron Nola with a 3-2 win, clinching the Phillies’ trip to the postseason. The two losses after that? Did you see the champagne-soaked party in the visitor’s locker room? Not to mention the “who cares?” aspect of those final two games? Note that the Phillies beat the Astros on Oct 3rd and when they met on Oct 28…the Astros lost again.

In just a few games, even a seven-game series, luck and weirdness play a bigger part than in the regular season. Here is where we have to give some serious consideration to the folks who object to the Phillies being here at all. The argument is that teams with a “better” W-L record deserve to be beneficiaries of that luck aspect. Well, how would the Milwaukee Brewers have fared? They only finished one win behind the Phillies. They also beat the Cards head to head, 9-8. They lost to San Diego 3-4. They split with the Braves, 3-3 (I thought these things were always odd numbers?). Given that they traded their closer to San Diego, couldn’t muster much offense, and added little at the trade deadline, I doubt they would’ve gotten past the Padres assuming they could have bested the Cards.

These same persons who don’t seem to understand baseball in either its long season or its postseason, would argue that somehow teams such as the Phillies just not be let into the postseason at all. The argument is vaguely similar to when I graded papers as a teacher and there was a clear break between the A and B students for a particular assignment. The problem is, it’s not just one assignment. It’s a 162-game season. Those who manage to show they’re capable of participating in the postseason have by definition earned their place. Would any team with a record worst than the Phillies have fared as well? Extremely doubtful. Therefore the argument against the Phillies is that given their record, they just shouldn’t have been granted a seat at the table. Were the Padres more worthy? They managed, over 162 games, to have won just two more games. Wow–a .549 winning percentage against the Phillies’ .537 percentage. Or would these same complainers be also upset at the Padres? Where is the line between “okay, they’re worthy” and “who the F are these guys”? As a teacher, I would draw a line between the Dodgers, Mets, and Braves, all of whom won more than 100 games, and the Padres, Cards, and Phillies who won 89, 93, and 87 games, respectively. But MLB has, rightly in my opinion, decided that teams who ‘right the ship’ two to three months through the season and have fought well head-to-head against the top three teams, all have a right to be vying for the title. Look again at the 100+ winners. These erstwhile Fanboys who think that record is everything, what do they have to say that the Mets would have been out of the postseason if not for the Wild Card format? You can’t complain about a format which lets the Mets in, but also lets the Phillies in.

There isn’t a formula for fairness. Baseball recognizes that no team’s performance over the regular season guarantees its success in the postseason. If it did, we wouldn’t have the postseason at all, except for the top NL team meeting the top AL team. (And even that is going to become less meaningful next year when schedules become more balanced.) The regular season exists to establish which teams have ‘grinders’ who will, day in and day out, make sure their team wins more than they lose. It’s up to the managers to make sure these grinders are playing. It’s up to upper management to make sure there are enough grinders on the team. These teams earn their ticket to the postseason. But the postseason is different.

Billy Beane famously said that the postseason is a crap-shoot. Lately though, pundits have wondered why a head honcho (president? general manager?) can’t craft a plan for the postseason. The two purposes, winning in the regular season and winning in the postseason, are at odds. I would argue that Dombrowski has started to manage that conundrum. He correctly realized the addition of the DH to the NL meant that offense meant more than defense (especially in the Phillies home ballpark). Did he realize that the defense would gel a bit? I don’t think so. He didn’t care; he just lucked out. He trusted his own ability to make moves mid-season. He added incrementally and skillfully, the way that Pat Gillick did when the Phillies went to the postseason in 2008 and won the World Series: he grabbed Edmundo Sosa from the Cardinals for a pitcher who pitched only 14.1 innings and wasn’t any good by any metric. Meanwhile, Sosa played in 25 games (out of the approximately 50+ games left in the season) and batted .315, with a nearly perfect record by defensive metrics. Dombrowski snagged a defensive gem of a player but struggling at the plate, Brandon Marsh, from the LA Angels and gave up a catcher who will likely play a solid career as a backup and occasional starting catcher (Logan O’Hoppe). He tapped the Angels again for Noah Syndergaard sending failed project Mickey Moniak and a pitcher who’s never pitched above low-A baseball. Seriously? Who makes trades like this? And to ice the cake, Dombrowski got David Robertson from the Cubs, parting with a promising, but again only-in-high-A ball pitcher.

Additionally, Dombrowski made a few additions by subtraction. He parted ways with Didi Gregorius, a .210 hitter on the season with a fairly crappy defensive record. Would Girardi have continue to play him, had he been around after June 3rd. Hell yeah! They both hailed from the all-wonderful Yankees! Never mind that Gregorius became available to the Phillies because the Yankees correctly recognized his best days were past. Dombrowski also said a not-so-fond farewell to Odubel Herrera, the maddeningly promising but never quite fulfilling the promise outfielder who had laid at least partial claim to the centerfielder’s position. And the final addition-by-subtraction? Designating Jeurys Familia for assignment. Three days later he latched on to the Red Sox. Over those two months he pitched only 10.1 innings and compiled a 6.10 ERA. Enough said about that.

And Dombrowski recognized that having adequate pitching, adequate fielding, and batters who could turn a game with a swing of the bat would be more valuable in the postseason. Multiple pundits have put forth that the team which has good pitching and hits home runs will win in the postseason. Maybe Dombrowski is onto something? Construct your team to score multiple runs when it can, and hope they do so in the postseason?

Philadelphia belongs in the postseason. The haphazard and perplexing schedule of 2022 made many a team a victim. The Phillies ‘hangover’ from its last General Manager left Dave Dombrowski with a mess prior to 2021. That he managed to correct it enough by June 3rd of this year and by August 2nd adjusted enough to get a team into the postseason is a testament to expert roster construction and an intimate knowledge of what the postseason is all about.

And it’s not all about who wins how many, contrary to the shallow fans who think the Phillies shouldn’t be here. The 19-game margin between the Astros and the Phillies represents less than 10 games which could have been won but were lost. In other words, 5.9% of the season. These fans would be well advised to consider the only other time that such a large margin occurred in the World Series: in the fourth year of the World Series, 1906, the Chicago White Sox finished the season with 93 wins (respectable) versus the Chicago Cubs’ record of 116 wins: a discrepancy of 23 wins (i.e., more than this year, folks). The White Sox won the championship, four games to two. Think about that, Houston, and all of you who think the Phillies don’t deserve to be in the postseason.

Kentucky oil study

Sage advice

“After writing a poem, one should wipe carefully and wash one’s hands.”

write me poetry (wriggling fish eludes grasp)

"Write me poems," she said. "Not that sonnet, rondeau crap. Make it formed, but not formal. Make it happy, poignant, heartfelt." Whew! Tall order. How to commit to words which don't bring despair, don't touch my psyche's crackling third rail? 'formed, not formal'? Wrapped around my neutrality entwine serpents of dark, of light, yet both truthful. One favors pain, despair, sadness. Countering, its mirror favors hopeful, joyous optimism. But it whispers-- 'gainst its brother-- screams less, asks more. "Everything's great!" doesn't cut it. Good news--no news. Seismic shifts, stabs to my heart grab more attention than goody-ness. Problems add edge, life's hoppy bite, offsetting its malty sweetness. But she challenged! Can happiness inspire poems? My life-garden hosts tangled plants, gnarled, tall, choking new growth. Little shoots blossom up regardless, and... Something happens. My ultimate Gardener, my concept of God nurtures sprouts, brings forth fresh flowers striving to vie with woody growths. Despite these new optimistic upstarts, my soul's garden remains wild: poison vines, weeds, burrs, thorns. No apologies. Who am I to question what grows, what does not? Why question my lived reality, denigrate my totality? Are we happy now? Are we mired in hopelessness? Do we focus on pretty new blossoms? Do we ignore the whole? Without yin there's no yang. Without black, white on white. Speak to truth no matter its source. Shuffle the deck; deal ALL its cards. Thirteen sevens multiplies two potent numbers, magical yet at odds with each other. She will appreciate [this].

On reading: a random list

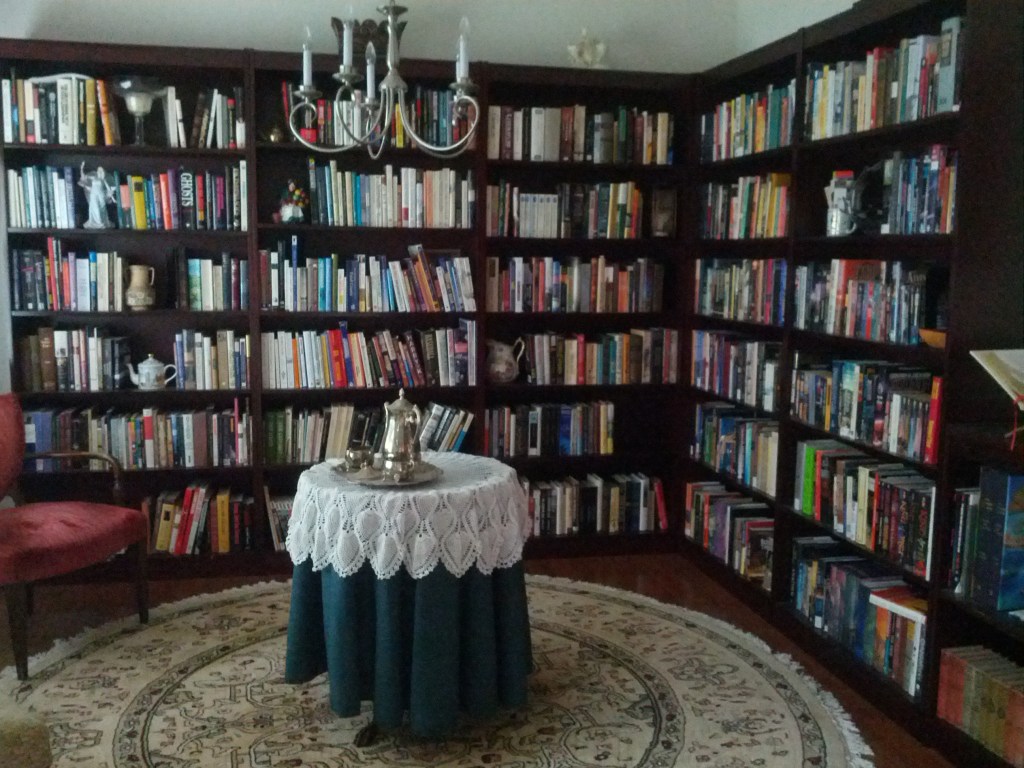

I’ve just finished entering my latest e-book purchases into my preferred library cataloging software, LibraryThing. Entering new books into the library brings joy, frustration, smug self-satisfaction, and fills me with an urgency for and desire to read. I’ve noted before my acceptance for “owning” books which I will never read, that in essence I spend minor amounts of money to reserve a book, for it to sit on my bookshelves real or electronic, to tantalize me and inspire me to read. But why?

Today I’ve 422 unread books. I suppose I’ll live another 20 years. That’s 21 books per year, and frankly I’ve disappointed myself with my slow pace of late. (On the other hand I’ve read 661 books on those shelves. I’m still ahead, right?) The combination of time remaining and still to be read has changed my reading habits. No longer do I tolerate and read mediocre books. I give them a suitable audition then cruelly call “Next!” to them. The definition of mediocre has changed too. No longer does this word represent quality, but rather suitability: perfectly respectable books which just don’t grab me get tossed aside. A good example is Ben Okri’s The Famished Road winner of the Man Booker Prize for literature in 1991. It purported to be the type of book I like, a meaningful fiction filled with magical realism. Yet it became tedious (likely by design) as I endured dream-chase sequences again and again. Finally, after a much longer audition than planned (four weeks), I read a plot summary and realized little of note was going to happen which I hadn’t encountered already. Goodbye, Mr. Okri. Thanks for the entertainment.

I’ve gone through a spate of this. Gore Vidal’s Inventing a Nation proved a sad disappointment after reading Burr and Lincoln, two other books in his loose series on American history. Though I peer dimly through the decades since I read Washington, D.C., from the same series, I remember it with admiration also.

I’ll use a random number generator to select ten unread books from my library to illustrate some points. But first let’s confess to liking some of the children less than others: books are categorized as “To read” but the ones I really want to read also sit in the “To read ASAP” category. Books to consider for my next read get special billing: “The Short List” whose members change with the whims of this reader.

Our first candidate is Gap Creek: The Story of a Marriage by Robert Morgan. It interests me little. I didn’t purchase it (my wife did), it boasts of inclusion in Oprah’s Book Club–not a kiss of death, but smacking of the detraction of populism for sure–and, sadly, because it is a physical book. Nearly all of my books of interest now are e-books, a whole ‘nother topic for ‘nother day. In its favor? According to The New York Times, it’s a “Notable Book” written by a professor of English, and this blurb from the New York Times Book Review intrigues: “At their finest, his stripped-down and almost primitive sentences burn with the raw, lonesome pathos of Hank Williams’s best songs.” (Let us pause and thank the NYT Book Review for properly writing the singular possessive form of Williams.) Chances of being read before I die? Around 25%.

Book #2: A Handbook to Literature assembled by C. Hugh Holman. Another physical book, likely picked up at a garage sale in the 1980s. This is not an anthology of literature as one might suspect from the title, but instead a type of reader’s encyclopedia. In this digital age, virtually superfluous. The fact I own Benet’s Reader’s Encyclopedia kills any chance I would have of reading anything in this book. (Why is it still on my shelf?)

Book #3: Empires of the Word: A Language History of the World by Nicholas Ostler. It promises to dish out a history of all of “the world’s great tongues”. I remain equally an amateur linguist and student of literature. It sounds interesting but one must consider the reading menu. Chances I read it? About 25%.

Book #4: Northanger Abbey and Persuasion from the Oxford Illustrated Jane Austen, volume five. Intellectually I want to say, “sure, I’ve read Jane Austen.” In truth I never have. Just didn’t get assigned in college courses, didn’t break through certain barriers I had as a youth when I read just about anything, and now fights against so many more modern and personally relevant books. On the other hand, I’ve read books from the 1800s to great enjoyment. Why not Austen? I don’t know. We’ve got the entire six volumes of it, plus I snagged Sanditon as an e-book. The chance I’ll read this particular book instead of Pride and Prejudice or Sense and Sensibility or Emma? Pretty much zero.

Book #5: Between Two Worlds (The Lanny Budd Novels Book 2) by Upton Sinclair. Tellingly, I react with, “Oh. That book.” Based on a well-written blurb once, I started collecting the entire 11-book series whenever one would be offered on sale. It seemed like a good idea. Not until I had all eleven did I read book one, World’s End. How disappointing. It made me want to cry or hit someone because instead of writing a story, Sinclair wrote a narrative about a story. Don’t tell me; show me. I’m still trying to figure out how this series could ever be considered as highly as it apparently was about 75 years ago. Chances of being read? 1%, based on the perception that “maybe book two is better than book one…even though I bailed on book one before I was done with it.”

Book #6: Antimony by Spider Robinson, a science fiction anthology of his short stories. I enjoyed reading his Lady Slings the Booze, but he has a tongue-in-cheek style of writing which is clever, not good. Watching someone settle for the easy, quick, and stereotypical would bother me now. The chances I’ll read a bunch of his short stories? About 10%.

Book #7: Writing Down Your Soul: How to Activate and Listen to the Extraordinary Voice Within by Janet Conner. It’s the first book here marked “to read ASAP” because it’s Amazon review quotes at the top, “I am a writer. Today I write.” This grabbed me when I couldn’t ignite this writing life. Now that I’ve done so (thank you, WordPress), I’m kinda turned off by this book. The author “discovered how to activate a divine Voice by slipping into the theta brain wave state…while writing.” Yeah, no. I’m out. And I’m dropping the ASAP designation.

We’re down to the final three contenders and nothing much to show for it…but here’s one at #8: The Ghost Road (Regeneration Book 3) by Pat Barker. The first book in this series, Regeneration, was nominated for the Booker Prize. Ms. Barker felt she had been typecast as a feminist writer so she undertook this trilogy about the First World War. It purports to weave history and fiction with doses of poetry, to throw real and fictional characters into the mix, and to address how war can be terrible yet valuable all at once. I’ve categorized it “To read ASAP”, and I’m looking forward to reading it, 100%.

At #9 we have…a quite intriguing book: My Grandmother Asked Me to Tell You She’s Sorry: A Novel by Fredrik Backman, translated from Swedish by Henning Koch. This is another “read ASAP” book. In this book Backman imagines a “different” 11-year-old girl who connects only with her crazy grandmother. Grandmother dies, leaving letters apologizing to people she has wronged. The granddaughter carries out her grandmother’s wish to have these delivered and experiences the connection between real and fable, experience and stories. I made that up, obviously since I’ve never read it, but I feel as if I have in an abstract sense. I yearn to read the details which underpin this story’s arc. Chance I’ll read it? 100%

Here we are at #10: New American Short Stories 2: The Writers Select Their Own Favorites edited by Gloria Norris. I can tell this physical book has sat on my shelves for 30-35 years as I’ve moved nearly a dozen times. Will I read it? The chances are a bit less than 50% because I’m not a big fan of short stories anymore unless they’re illustrative of a great writer.

There you have it. As a 27-year-old I was challenged by a professor well past her retirement age to consider the judgment of time regarding the “greatness” of an author and of a work. I slowly came around to her idea as I put more years behind me–I know several works which smacked of greatness back then now seem merely good. That’s not to disparage them, but they seem embedded in their time, incapable of providing the illuminating experience which truly great works command. Some recent (past 100 years) authors exist there already: Jose Saramago, Carson McCullers, Italo Calvino, Lawrence Durrell, Jim Harrison, Ernest Hemingway, and Gabriel Garcia Marquez to name but a few. Some contemporaries–F. Scott Fitzgerald, Donald Harington, Hortense Calisher, Annie Proulx, Neal Stephenson, John Irving, and the just mentioned Fredrik Backman–must wait until the jury renders its verdict, likely not in my lifetime. We read, though, for our own enlightenment, our own enjoyment, and our own sense of needing to connect with more than we are. We write for those same reasons. We need make few, if any, excuses for reading or writing the works which will do that for us.

the poet upon reading poems written by those who follow his

Just buggy

Reading into fandom

[Part three of my Baseball Fan Trilogy. Parts one and two detail the general world of Phillies Phandom and then my development into one, respectively. All hyperlinks to Wikipedia will go instead to mirror site Wikiwand. Be forewarned.]

What does one do when he finds himself obsessed with a sport? How did this happen? How can a non-athletic sort explain to himself, let alone others, how he’s accepted the cognitive dissonance caused when his obsession for a sport coexists with his disdain for the jocks he’s encountered throughout his life? (And how much does this explain other such dissonant aspects of his reality?)

I wish I could tell you. Others have found themselves in similar traps: the accommodations are acceptable but one realizes escape remains impossible. We therefore tell our fellow captives what wonders our trap displays, how surely it transcends all other traps, about the beauty it exhibits and instills, how ultimately this trap must be an allegory for heaven…anything to justify dancing around our living rooms (with or without audience) when our chosen team sends a little white ball a few hundred feet and ignites an improbable run to a championship meaningless to anyone outside of the trap.

One of our more prominent captives, George F. Will, took a shot at explaining what the basic participants–managers, pitchers, batters, fielders–think about when they apply their talents to the game. His words continue to be quoted by the obsessed, one to another.

One of the best baseball wordsmiths, Thomas Boswell, wrote How Life Imitates The World Series in 1982, although in truth it collects columns he wrote prior to that for The Washington Post. If George Will is a dry-as-dust baseball intellectual (who also wrote for The Post but as a political pundit), then what are we to make of his quote on the cover of Boswell’s book? “The thinking person’s writer about the thinking person’s sport.” Those words set a high bar. Boswell clears it. His very first entry in the book is “This Ain’t a Football Game. We Do This Every Day.” Deeply down the rabbit-hole by the time I read the book, you will have to pretend to understand my thrill at its first sentences:

“Conversation is the blood of baseball. It flows through the game, an invigorating system of anecdotes. Ballplayers are tale tellers who have polished their malarky and winnowed their wisdom for years. The Homeric knack has nothing to do with hitting the long ball.

“Ride the bush-league buses with the Reading Phillies or the Spokane Brewers or the Chattanooga Lookouts, and suddenly it is easy to understand why a major league dugout is a place of such addictive conversational pleasures.”

He had me with that last sentence. I’ve watched the Reading Phillies, the Double-A affiliate for the Philadelphia Phillies. I grew up in Spokane. I’ve been unable to confirm Boswell’s contention that a team there ever bore the name “Brewers” since the Spokane Indians were founded for the 1903 season and have been the Indians ever since. But look what just happened. Boswell and I now have a conversation going on, even though he doesn’t know I exist. It starts with a common love for baseball.

Boswell in his column announcing he wouldn’t cover the 2020 World Series due to worries about Covid-19–he was 72 at the time–wrote that he decided to remain a journalist with The Post due to covering the dramatic game six of the 1975 World Series where Carlton Fisk hit an historic home run. “Where would I be today if Fisk’s ball had gone foul?”

Where indeed? We understand, Mr. Boswell, those of us down this same rabbit-hole of a trap. I started digging ever deeper into the tunnels about 20 years ago when I read Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game by Michael Lewis. Though entertaining, the movie does little justice to the deeper tropes of the book. In the book, Lewis expertly relates how eventual Oakland Athletics General Manager Billy Beane attempts for years to explain to himself how he could have had such promise that the New York Mets drafted him in the 1st round (23rd overall), yet he flamed out with little to show for all those predictions of greatness: he played regularly only one year in the majors (1986) with a few plate appearances in five other years 1984-1989. His career batting average was .219 with a fielding percentage to match.

During that same time he played with Darryl Strawberry who the Mets drafted #1 overall in the same year they took Beane at #23. Theoretically the two should have enjoyed a friendly rivalry, spurring each other on to the big leagues. In actuality, Strawberry got there a year earlier than Beane. Strawberry played regularly as soon as he entered the majors, and played from 1983-1999 with eight appearances in the All-Star game. Beane had his one “good” year in 1986, when Strawberry earned his third trip to the All-Star game.

Beane deduces that the scouts basically screwed up when they thought he possessed talents anywhere near Strawberry’s. He learned of the nascent movement to quantify baseball more with advanced statistics when Sandy Alderson, Sr., handed him a pamphlet from Bill James one of if not THE pioneer of sabermetrics. And then he…ah, but there I go down the rabbit-hole again. Sorry.

Early in my baseball initiation I read Prophet of the Sandlots: Journeys with a Major League Scout by Mark Winegardner. Winegardner follows Anthony “Tony” Lucadello who scouted for over 50 years, first for the Chicago Cubs and then for the Philadelphia Phillies and–wait what? The Phillies? Okay, I’m in. A great piece of irony occurs when the book details Lucadello’s pursuit and signing of Mickey Morandini, but the book’s appendix doesn’t list him on its list of Lucadello signees who played in the majors. Why? Because Morandini, who starred at second base for the 1993 National League Champion team, didn’t make the Phillies until 1990, the same year the book was published. Lucadello signed 52 players who made it to the majors including Ferguson Jenkins and Mike Schmidt. The description about how he finds, nurtures, and convinces Morandini to sign with the Phillies justifies the cost of the book.

Most baseball books do one of two things: they explain the aspects of the game or they serve to record for posterity’s sake the great teams and individuals of the game. A few overlap between the two, such as Men At Work mentioned previously. A few, though, do neither. They illuminate the soul. I purchased Baseball As A Road To God: Seeing Beyond The Game by John Sexton in hopes of illumination. I left the book educated, provoked, but ultimately unsatisfied. I mention it here to show the lengths to which baseball fans who are also erudite readers find themselves pursuing to satisfy their urges. Sexton taught (still teaches?) a course at New York University on the same subject as the book. He writes about the shared aspects between baseball and religion. I saw the similarities. I didn’t see how baseball gave me a road to God in the Buddhist sense of many paths/one goal. But the 4.5 star rating on Amazon indicates many have found the book worthy.

More often baseball aficionados like to read about the nooks and crannies of the sport. One such book is Dan Barry’s Bottom of the 33rd: Hope, Redemption, and Baseball’s Longest Game. For those who know little of baseball, a regulation game is nine innings long. Both teams get a chance to bat against the other, the visiting team going first in the top half of the inning. The home team follows in the bottom half. If, however, the score is tied at the end of nine innings, the two teams keep playing. Baseball does not tolerate ties (except when it does, albeit rarely). A Triple-A game between the Pawtucket Red Sox and the Rochester Red Wings started on a Saturday prior to Easter Sunday 1981, and it seemed neither could score on the other–wait that’s not true! Both teams scored one run in the 21st inning! Baseball’s participants adhere to the game’s rules with the same religious fervor as those attending Easter Sunday services. Because no one could raise the league’s commissioner–the only person allowed to suspend the game–they played on. And on. And on. When it ended around dawn the next day, the teams had played nearly four games’ worth of innings. Future stars Cal Ripken, Jr., and Wade Boggs were players in the game. Future manager Bruce Bochy also was there.

Since Jim Bolton’s Ball Four, baseball books written by former or active players tend to be much more jocular and comically entertaining. Former relief pitcher Dirk Hayhurst has written four such books. The first, The Bullpen Gospels: Major League Dreams of a Minor League Veteran, remains the best from the standpoint of providing both entertainment and insight. In it, Hayhurst gives us his anecdotal account of being part of a Triple-A bullpen, hoping one day to play in the majors. I constantly think about his description of a sudden, late-season callup from the Portland Beavers to the San Diego Padres–not for his description of the play but for his Oh-My-God reaction to all the perks major league players get. Hayhurst spent all of 39 and one third innings in the majors, or approximately six innings longer than that Triple-A game in Pawtucket a quarter century prior. Somehow he managed to parley his constant conversation into a commentary role on several broadcasts.

In the same vein but more parochial lies The 33-Year-Old Rookie: How I Finally Made It to the Big Leagues After 11 Years in the Minors by Chris Coste. The novelty of a player languishing in the minors for over a decade yet never appearing in the majors at any time seems unbelievable to anyone who follows the sport. Few would stick it out that long, for one. However Coste played catcher, a coveted position making him instantly more valuable than just about anyone else on that Triple-A team. Relief pitchers with any promise have been called up long before their 33rd birthday. Starting pitchers have been converted to relief pitchers (see last sentence). Position players have been let go to clear the way for younger, more promising players. Coste pigheadedly played in independent leagues from 1995-1999, which is just crazy. To the best of my knowledge no one has ever made it into the Major League Baseball system of minor leagues by spending five years in independent ball right out of high school or college. Coste, however, managed to get signed by the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1999, briefly, but wound up playing independent ball again that year. In 2000 he latched onto the Cleveland system, playing AA and AAA. In 2003 he moved to the Boston system, in 2004 to the Milwaukee system. In 2005 he signed with the Phillies, playing AAA in Scranton-Wilkes Barre. Scranton-Wilkes Barre now hosts the Yankees’ AAA club but was affiliated with Philadelphia at the time. And in 2006 he got “the call”.

Adding to the book’s value, Coste just didn’t make it to the majors at age 33, but when he got there he stuck there. This never happens for a backup player called to fill a minor gap at age 33, yet alone for a player who spent 1995-2005 just scratching his way toward yet another AAA assignment. Adding an extra layer of enjoyment: when Coste joined the major league club, he backed up starting catcher Mike Lieberthal the long-time symbol for futility for the Phillies. Lieberthal was the backup catcher for 1994-1996 right after the team went to the World Series, and then guided the pitching staff through 2007, the first year the team again tasted the postseason. Coste continued with the team in 2007 and 2008 when Carlos “Chooch” Ruiz solidified his claim to the dirt behind home plate (edging out the unlucky Lieberthal who retired). In 2008 Chooch helped lead the Phillies to their first Championship in 28 years. For a Phillies fan, this book is like being told you’re getting a triple-fudge chocolate cake and then seeing it’s iced with the richest frosting imaginable AND IT HAS ALCOHOL-INFUSED BON BONS ON TOP! (Well, at least for this Phillies fan.) Coste was traded to Houston in mid-2009 and that year was the end of his major league appearances. Want some extra ganache on top, Phillies Phan? Coste attended Concordia College in Morehead, MN, just across the river from Fargo, ND. My father had many close relatives living in or near Fargo, and his mother graduated from Concordia. My best friend in high school attended Concordia. Ah, sweet serendipity!

If we spend time going through my entire bookshelf of baseball books, it will be like those times you got stuck in a promising bar only to allow the bar’s resident know-it-all bore you tears because he promises you free drinks: a terrible price to pay for only mild enjoyment. Let’s just mention one more. My most recent baseball read occurred this year and takes its place alongside some of the best I’ve read: The Baseball Whisperer: A Small-Town Coach Who Shaped Big League Dreams by Michael Tackett. The subject matter nearly overpowers the author’s skills to tell it, but transports nonetheless. The book profiles Merl Eberly who coached a summer college league in Clarinda, Iowa. College summer leagues serve two purposes: (1) young players getting ready to enter college or just beginning their college baseball careers often need some extra work–or to showcase their abilities; and (2) college leagues use wooden bats where the colleges (and high schools prior to them) have provided only metal bats for their players. Metal’s makes getting hits easy; wood…not so much. In the middle of cornfields and nowhere, Eberly guided and developed many young players. Among them were future stars Ozzie Smith (15-time All-Star and Hall of Famer) and Von Hayes (1989 All-Star and a Phillie when the team went to the World Series in 1983). Tackett’s ticket into the story occurred when his son wanted to play for Eberly. The Iowan coach may resemble a small-town John Wayne–and Clarinda is only a 90-minute drive from John Wayne’s hometown of Winterset–but his compassion tempers his strict, disciplinarian approach. There were moments I wiped tears from my face, but I will not spoil it for you. As MLB.com stated, “Field of Dreams was only superficially about baseball. It was really about life. So is The Baseball Whisperer… with the added advantage of being all true.”

I’ve failed to capture the elusive spiritual, pulse-of-life truth baseball holds forth for the seeker willing to dive deeper than comparing statistics or reading yesterday’s scores. To those such as myself, joy may be found on Little League and high school diamonds; pulses will quicken when we hear a horsehide-covered hardball strike a leather glove at 90-some miles per hour or hear that same ball meet a loosely swung round piece of wood; irrespective of having watched a game, we will dive delightedly into someone’s scorebook of it which bears esoteric notations known only to initiates; or our anticipation will leap when we hear our team’s signature sound bite of music blare from the TV, announcing another game getting ready to begin. These things remain elusive. Lao Tzu describes it best in the opening to the Tao:

The Tao that can be told is not the eternal Tao.

The name that can be named is not the eternal name.

This inability to fully communicate our forays into the mystic joy of baseball lies at the heart of one of my fellow captives in this rabbit-hole trap, and one of Major League Baseball’s commissioners. Professor of English Renaissance literature, president of Yale University, and seventh Commissioner of Major League Baseball, A. Bartlett Giamatti explained it this way:

[Baseball] breaks your heart. It is designed to break your heart. The game begins in the spring, when everything else begins again, and it blossoms in the summer, filling the afternoons and evenings, and then as soon as the chill rains come, it stops and leaves you to face the fall all alone. You count on it, rely on it to buffer the passage of time, to keep the memory of sunshine and high skies alive, and then, just when the days are all twilight, when you need it most, it stops.”

[translation of Tao Te Ching by Gia-Fu Feng and Jane English, copyright 1972. Giamatti’s quote from “Take time For Paradise: Americans and Their Games”]

What I’m reading 221019

After setting aside three works to which I did not measure up, I’ve picked up a tried and true author (for me), Jose Saramago. Two days of reading Journey to Portugal has set my world aright. Fine writing will out, and regardless what others may say, most works are not fine. In this book’s case, exquisite writing offsets its meager “plot”. But I’m only into its beginning pages; perhaps it develops in time.