Recently I participated in the funeral mass for a dear choir friend, a fellow bass voice. Dennis marked 85 years, all of them vibrantly alive, until his death on December 7th. I’m not sure why five weeks elapsed before the funeral mass. I surmise the travel logistics of a few participants whom he hoped to have at the mass played a large part: the homilist had attended seminary with Dennis. Likely he wanted everyone to be focused on Christmas, not himself. He was like that. I’m not writing this about Dennis and the funeral, however.

One theme predominated in the mass. Dennis believed with every fiber of his being that being Christian meant fostering community in all its aspects: helping the poor; supporting the rights of those downtrodden; welcoming the immigrant; supporting the abused, the sick, the dying; and being open and unjudging to all with whom he came into contact. “Sounds almost priestly,” you might say, and you would be correct. Dennis trained for the priesthood and in the mid-1960’s he received ordination into the Roman Catholic rite as a priest. Though he left the priesthood soon after joining a parish, he never stopped being a spiritual advisor.

He told me two years ago that in the first years of priesthood he became disillusioned with the elder priests he encountered. They had no regard for their parishioners as equal members of the body of Christ; they spoke condescendingly and disparagingly of them. He left the priesthood, married, worked in human relations and later as a small businessman, fathered children, and retired to the Raleigh area. But this also isn’t why I write these paragraphs.

After you buy a specific model of car, you suddenly start noticing the same model seems to be driven by every fourth or fifth driver you meet on the roads. In the weeks surrounding the funeral I keep encountering references to community, descriptions of community, lessons about community, and prayers about community. It’s difficult to convey the import of this. It’s not like hearing the new buzz word of the month on everyone’s lips. The concept of Community is fraught for Christians, I’m realizing. Dennis knew this. His belief in community basically formed the third rail of his life’s train, the one which carries the current. He accepted everyone, although he had a few choice words for those at the altar (the cathedral rector acknowledged in his closing remarks that he heard these choice words more than once from Dennis). This stirs me, agitates me, scares me. If my Final Judgment (in whatever form that may take) will rest on my participation in Community, I’m screwed.

I’m not a “reaching out” kind of person. Introspective might be the wrong word, but I’ll go with it. (Borderline sociopath? Asocial?) I’m quite content left to my own devices, have been since I stood on the threshold of puberty. As a young man I often spent my weekends without uttering any words except to my cat. I can recall needing to prime my lexical pump to talk to people on Monday. My poor wife has learned to her detriment that her husband at times seems to need no one, and has learned to nudge me to do a few things to fulfill her need to be an Actual Social Being. One of the best things to happen to me occurred when I quit being a reporter/editor for weekly newspapers and entered teaching. Teaching requires constant talking and fostering a learning environment. My methods professor likened it to performance—well, technically to being a performer in a circus. I concur. Ultimately I learned playing in outgoing roles does not an Outgoing Person make. Solitary is still solitary; introversion will out.

As I think about the logic of fostering community (the Body of Christ, after all), I contemplate some other close friends and family, wondering about their ability to balance their need for seclusion with the compulsion to reach out to others. My Raleigh compatriot calls himself an introvert, but he’s a different one than I. In restaurants he specifically learns the server’s name and uses it. He makes it a point to engage other patrons at our local watering hole. Where I would banter superficially with a bartender and local barstool denizens—teachers become glib, after all—he engages in Real Conversation. Once we were outside Chef and The Farmer, a restaurant in the small city of Kinston, NC, and made famous to those who watched A Chef’s Life on PBS. A cameraman had his rig set up on the front walk, taking scene shots apparently for the show. In that situation I’m content to observe, “Hey, look, they’re filming for a new episode,” and maybe giving the cameraman a thumb’s up. My buddy walks straight up to the guy to verify he’s shooting for the show and to tell him how much he likes the show. Heck, maybe more, I don’t know. I didn’t accompany him. He traveled to Guatemala several times with a group from our church and rounds them up on a monthly basis for dinner. He makes friends of the people he encounters on his morning walks. I encounter people on my walks too, perhaps the same ones since we live in the same neighborhood. I know them only by face. They know me by my curt nod or an energetic “good morning!” and nothing more.

My father also followed this model. He never said, “I’m an introvert,” but he sure seemed to be happy enough being by himself most evenings. (I’m sure it wasn’t to get away from his two smart-aleck boys or the TV playing shows he didn’t like!) He also made sure to know all of his neighbors and greet them, boisterously, whenever he saw them. He really shone at church on a Sunday. As a PK (preacher’s kid) he truly believed in the community of Christ. He also grew up embarrassed that his father the minister couldn’t remember his parishioners’ names. Apparently he swore to never let that happen to him. Me? It’s almost like I try to not learn a person’s name—they bounce off of me like sleet on a tin roof. As I near eight years in this house, I don’t know the name of my neighbor to the south. The one across the street is named Tom…I think. I’ve only spoken to him once, when we first moved in, and I’m pretty sure he realized I was going to be “one of those” who didn’t interact with his neighbors. My neighbors to the north moved in shortly before the pandemic. I met the husband when he started to take down the fence between our yards. I know his name. We talk at length a few times each year. It helps that he’s open and friendly, plus he’s Roman Catholic also and his wife teaches music in Catholic schools. Obviously, though, I’m not my father.

If I were to compare myself to someone, it would be the talk show host Johnny Carson. I read somewhere he claimed to be an introvert who could interact conversationally quite well, but who preferred being alone. I fear Carson’s notoriety for being a person difficult to be around also applies to me. Me? I’m starting to grapple with the idea I may have to up my game if I want to be called human. I’ve always identified with Sheldon in Big Bang Theory, not because I’m a super-genius but because I tend to think I’m smarter than those around me and I find interacting with people painful at times. Perhaps I should have led with that. I think we can support and grown community in many different ways, but at the same time I’m going to work a bit harder on learning names, being a bit more accessible, reaching out.

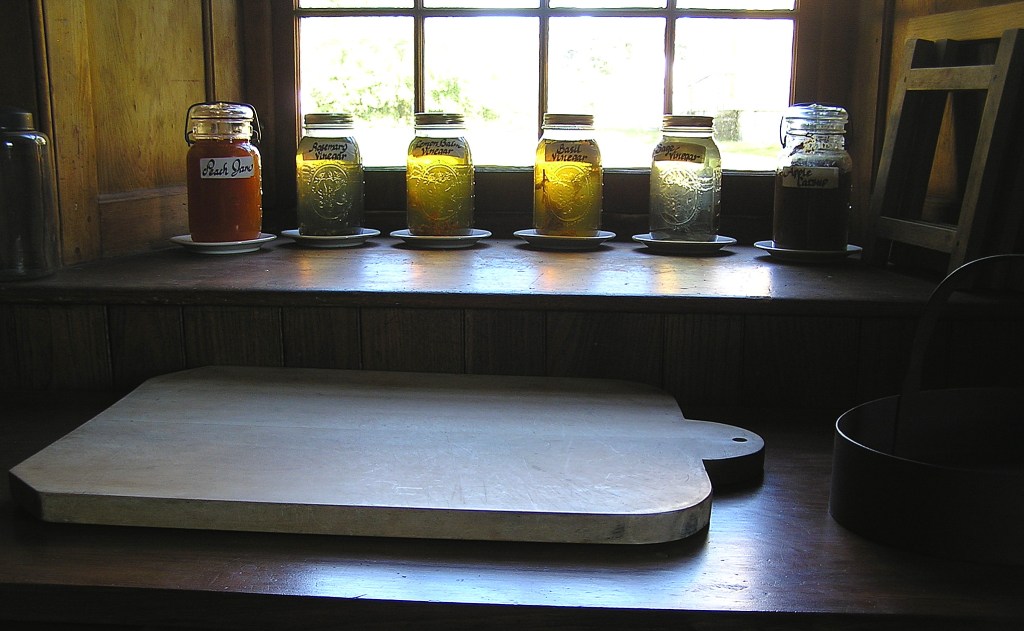

A note about the photos: Community shows in a variety of ways. In September 2004, my parents visited us in upstate New York where we lived east of Troy in the foothills of the Berkshires. Tucked at the end of a long dirt road, a Buddhist nun lived at and attended to a stupa. I’ve no idea how it came to be, but find the juxtaposition interesting: feeling connected to all beings, they built a stupa in a township of fewer than 2000 persons. By contrast, the Shakers may have drawn themselves into a segregated community, but were much more accessible to the general public. Mostly, though, I think on my father who looked constantly for people to connect with. The calm stillness of a pond might represent his interior, but he always made time to foster community and strengthen it…as described above.