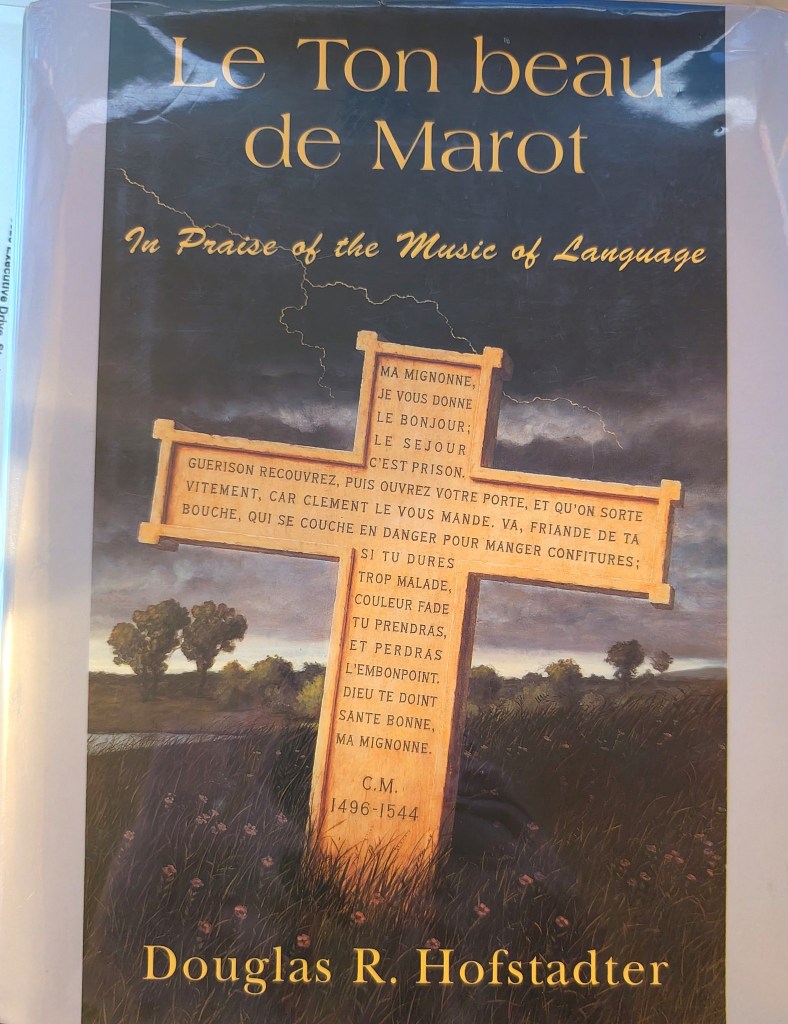

Having published a book review just an hour ago, it seems fitting to revisit my Bibliophilia series with what amounts to another review. Le Ton beau de Marot: In Praise of the Music of Language by Douglas R. Hofstadter impressed me to such an extent that I purchased another when I lost the book to a less-than-responsible work friend. For nearly a decade it bothered me that I couldn’t pick it up and show it to people when I said, “you’ve got to read this!” Finally, having purchased Hofstadter’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Gödel, Escher, Bach: an Eternal Golden Braid (which has proved so dense I’ve never finished it), I tracked down a used version of Marot from a bookstore in Santa Fe, NM. (I necessarily bought it used because it apparently was out of print.) It’s inching its way up the Read Me list, probably gaining the top position in 2026. But why gush about it? To answer that, I must detour to 1999.

In July 1999 my wife received news that the lump in her breast was a benign cyst, nothing to worry about. A little over a month later she received word that the tests had been mixed up and that she actually had cancer. This occurred on her birthday. After three surgery procedures in September, we took a vacation to the Oregon Coast just one week prior to her beginning the chemotherapy regime. We stayed in a wonderful condo on Yaquina Bay at Newport, OR. When we left, we took a leisurely drive up Highway 101 along the coast all the way to Astoria before turning east the next day toward home. Shortly before we arrived to Astoria we stopped at Seaside when a largish bookstore caught our eyes. There I found Hofstadter’s book. Loving language, I read the flap, learned it took up the challenge of translation, and that it also touched many other topics. From the flap:

…he not only did many of his own translations of Marot’s poem, but also enlisted friends, students, colleagues, family, noted poets and translators—even three state-of-the-art translation programs!—to try their hand at this subtle challenge.

The rich harvest is represented here by 88 wildly diverse variations on Marot’s little theme. Yet this barely scratches the surface of Le Ton beau de Marot, for small groups of these poems alternate with chapters that run all over the map of language and thought.

Not merely a set of translations of one poem, Le Ton beau de Marot is an autobiographical essay, a love letter to the French language, a series of musings on life, loss, and death, a sweet bouquet of stirring poetry—but most of all, it celebrates the limitless creativity fired by a passion for the music of words.

What the flap only hints at I learned later. During the time Hofstadter gathered his many translations by consulting all those people, his own wife was dying of cancer. Thus, his “musings on life, loss, and death” dive deep into his soul and therefore ours. Add to that my own wife’s tussle with cancer—she won, unlike Hofstadter’s wife—and the work compels. As I worked my way through the book, I found it dealt with language at a very basic level some of the time: how do we mean things? How does one language differ from another? How does cognition play out in word choices? And on, and on…

When I finished it, I felt Le Ton beau de Marot had been one of the best books I’d read because it didn’t just deal with language or cognition or love or translation or meaning or any other of those things mentioned above. It dealt with all of them! I loaned the book to a co-worker whose daughter was headed off to college to pursue a degree in English and who wanted to be a writer. I undoubtedly didn’t make it clear enough that one day I expected the book back. When I handed it off, though, I held back my gloss notes, which instead of writing into the book I had written out on fine paper. (They were too extensive to write into the margins anyway!) The book meant so much that I still have the notes a dozen or more years later. Here’s one:

[p. 138-139] I would side with Frost, that poetry is what’s lost in translation. Not that it can’t be re-discovered in the new language, but it’s not the same poem. Thus the poet-translator is intent on supplying a twin, not the real thing.

Hofstadter’s work combined with my college readings on communication, media, and meaning to form my personal philosophy and understanding of all types of translation. I “see” the issue of meaning more deeply than many I engage with when discussing how a work translates from one language to another, how people in different cultures perceive things, how books become movies and vice versa, even in how Superman or Batman is translated every decade by a different director all of whom seemingly work from the same “text”. I even see the problems of translation as one of the issues currently plaguing United States politics.

Hofstadter’s book satisfied on so many levels, engaged so many pleasure neurons, that I can’t do it any justice. You’ll simply have to read it yourself if you love reading about language and the problems of translation…and cognition…and…