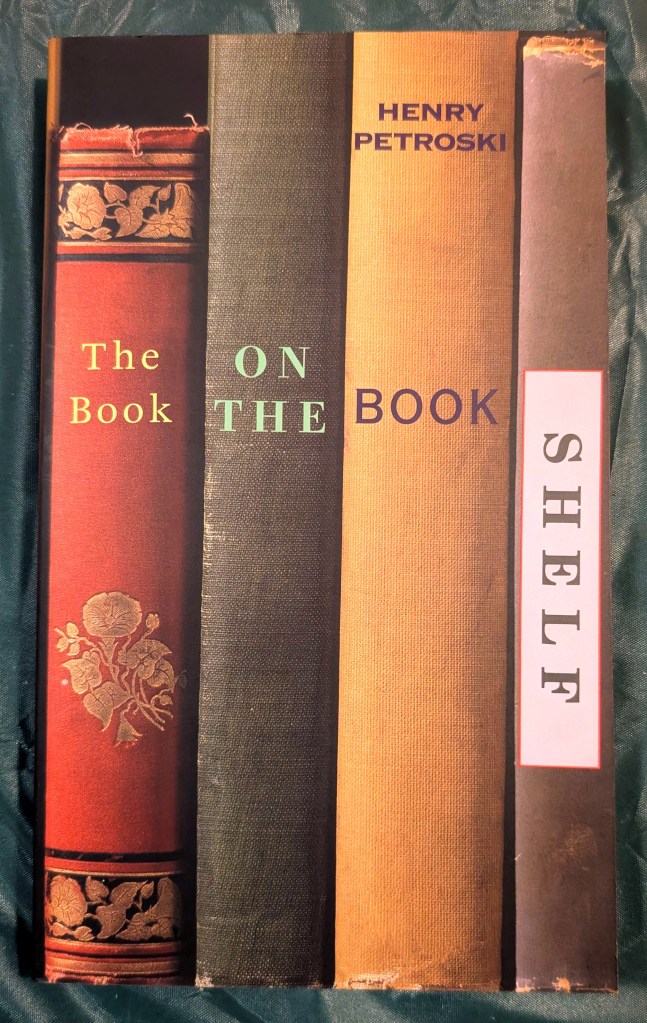

People who truly, truly love books, love books about books. One of the most unique of these appears above. Henry Petroski’s book The Book On The Bookshelf traces the history of books from their earliest inception as scrolls through the Middle Ages when they were chained to the shelf, and proceeds in its history to the present day. It’s a lovely read. Petroski winds up the book with a chapter about bookshops, another on the shelving of books, and a final one about the care of books.

The phrase “books about books” includes those about reading them. My original photo for this Bibliophilia subplot is repeated here:

In the semi-arbitrary manner I use to organize my bookshelves, books about books (and reading them) precede those which address English and languages. Alberto Manguel, an Argentine-Canadian writer (and translator, editor, essayist, and director of the National Library of Argentina) has two entries, both wonderful. A History of Reading celebrates the reader. With chapters such as “Being Read To” and “The Missing First Page” Manguel explores all of the aspects of the author-reader experience. Manguel divides the book into two sections: “Acts of Reading” and “Powers of the Reader”. I particularly liked this second section with its chapters of “The Author as Reader” and “The Book Fool”.

Manguel’s other book, Into The Looking-Glass Wood contains essays about books and reading. These range more widely than his History of Reading. Essays include reviews, reactions to other authors, browsing for books, essays about wordplay, and other more wide-ranging topics.

Ronald B. Shwartz’s book For The Love Of Books gets included here, simply because it’s on the shelf, and I can’t bear to part with it despite its shortcomings. I’m not one for the types of books which sample a range of acclaimed artists about a certain topic. This book gets the subtitle “115 Celebrated Writers On The Books They Love Most”. Yeah, so? What makes their opinion better or even equal to the critic for the New York Times Review of Books? Or any literature professor at dozens of highly regarded universities? Or, frankly, me? Regardless, I succumbed when I saw the authors cited include Joyce Carol Oates, Michael Ondaatje, John Irving, Bruce Jay Friedman, Doris Lessing, Norman Mailer, Witold Rybczynski, Kurt Vonnegut, John Updike, and Gay Talese. (Actually…I’m not sure I’ve ever completed this book! It still captures my imagination, and thus, it remains on my shelves.)

There you have it, books about books. If we can happily descend into the depths of books about books, how dare we deplore those who delve into the backgrounds of various oeuvres such as Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings? A nerd is a nerd is a nerd…